As we prepare our bodies for upcoming running events across Sydney, we have likely begun to up the ante on the distance, speed and intensity of our runs. But what does the literature support, and how best should novice runners safely increase training loads for an event while preventing injury?

Running-related injuries (RRIs) are common in all runners, with up to 50% of runners sustaining an injury each year that prevents them from running for a period of time, and 25% of runners injured at any given time. However, structured strengthening exercises and gradual builds in running distance can allow us to safely progress our running loads while keeping injury at bay.

Injury prevention

Considering the high rates of RRI in runners, injury prevention must always be considered as a part of training.

A systematic review conducted in 2014 collected data from 25 trials, which included 26, 610 participants with 3464 injuries. The study aimed to determine the effect of physical activity through strength training, proprioception (sense of balance and position in space), stretching and combinations of these exercises on reducing acute and chronic sports injuries.

Total estimate forest plots. Stretching demoted by red, proprioception yellow, strength green, and multiple component studies blue. Plots further to the left indicate higher effectiveness in reducing sports injury. Figure retrieved from Lauersen, et. al, 2014.

Analysis of the data concluded that multiple exposure (or, multiple interventions), proprioception training and strength training had a minimising effect on both acute and overuse injuries. In fact, strength training reduced sports injuries to less than a third, and overuse injuries almost halved. Stretching, however, proved no beneficial effect.

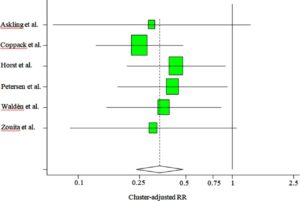

A more recent systematic review conducted in 2018 assessed the effect of strength training-based sports injury prevention specifically, and also attained favourable results. Six high-quality studies including 7,738 participants were analysed.

Forest plot of strength training sports injury prevention programs. Plots further to the left indicate higher effectiveness in reducing sports injury. Figure retrieved from Lauersen, et. al, 2018.

While implementation of the strength training programs varied between studies, its effectiveness on prevention of acute and overuse sports injuries was consistent. Overall, strength training programs reduced sports injuries by 66%, and were able to more than halve the risk of sports injury (with 95% certainty). A dose-response relationship between strength training and injury prevention was found, indicating that the more strength training was present, the better prepared the athlete and less chance of injury. There were also zero adverse effects due to strength training across all the studies.

Strength training should first begin with a familiarisation or technique phase, before increasing volume and intensity. Following this, the evidence suggests:

For preventing acute injuries:

- Strengthening failure thresholds of relevant tissues

- Technique and psychological preparedness

For preventing overuse injuries:

- Gradual tissue conditioning

- Sufficient technique

- Training variation

Talk to your physio about how best to initiate and progress your strength training program for optimal injury prevention and management.

Main take-away: Prevent injuries with strength training, focussing first on familiarisation, followed by gradual conditioning of relevant tissues with adequate volumes. Addressing technique, psychological preparedness and ensuring training variation are also crucial to integrate into your training program.

Progressing your training

Careful progression of training loads, primarily defined by weekly distance, also plays an important role in injury prevention.

A 2014 study followed 873 new runners for 1 year and compared those who sustained an RRI to those who did not depending on their weekly increase in running distance: <10%, 10%-30%, and more than 30% in the 2 weeks prior to injury.

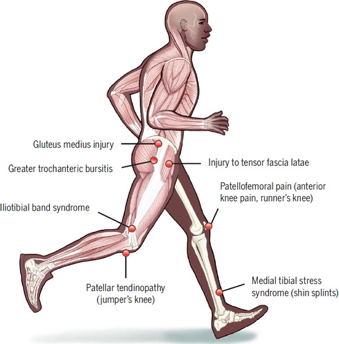

The study found that runners who increased mileage by more than 30% had increased injury rate than those who increased their mileage by <10%. Runners who ran longer distance at a faster pace had higher rates of patellofemoral pain (deep knee pain), iliotibial band syndrome (side knee pain), shin splints, patellar tendinopathy (front knee pain), greater trochanteric bursitis (hip pain) and injury to the gluteus medius or tensor fascia latae (hip muscles).

JOSPT Perspectives for Patients, based on Nielsen, et.al, 2014.

Other injuries like plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinopathy, calf injuries, hamstring injuries and stress fractures were not linked to the 10% rule and may be related to other training errors such as pace, increases in speed or sprint training.

Your physio can assist you in creating a personalised running program to help you achieve your goals while keeping injury away.

Main take-away: progress your running mileage by less than 30% over a 2-week period.

References

- Kakouris, N., Yener, N., & Fong, D. (2021). A systematic review of running-related musculoskeletal injuries in runners. Journal of sport and health science, 10(5), 513–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2021.04.001

- Lauersen, J. B., Andersen, T. E., & Andersen, L. B. (2018). Strength training as superior, dose-dependent and safe prevention of acute and overuse sports injuries: a systematic review, qualitative analysis and meta-analysis. British journal of sports medicine, 52(24), 1557–1563. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099078

- Lauersen, J. B., Bertelsen, D. M., Andersen, L. B. (2014). The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Sports Medicine;48:871-877.

- Nielsen, R. Ø., Parner, E. T., Nohr, E. A., Sørensen, H., Lind, M., & Rasmussen, S. (2014). Excessive progression in weekly running distance and risk of running-related injuries: an association which varies according to type of injury. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy, 44(10), 739–747. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2014.5164

- Fokkema T, de Vos R, Visser E, et al. Enhanced injury prevention programme for recreational runners (the SPRINT study): design of a randomised controlled trialBMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2020;6:e000780. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000780