Concussion injuries occur frequently in adults and children participating in contact sports and can also occur within the community setting or school playground. The ability to detect if someone may be mildly concussed can be challenging for practitioners and the likely rehabilitation times and recovery processes are not widely known even within the health industry.

My role as physiotherapist at the Claremont Football Club includes concussion identification and assessment, appropriate referral to an experienced medical practitioner, then facilitation of a specific neuro-rehabilitation program involving balance, coordination, and a step-by-step return to school and physical activity in conjunction with the treating doctor.

WHAT IS A CONCUSSION?

Concussion is defined as a complex pathophysiological process affecting the brain, induced by biomechanical forces (direct or indirect force to the head).

Historically the term relates to “shaking” of the brain within the skull, with resultant clinical symptoms not necessarily related to a pathological injury shown on imaging.

Concussion is a type of mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), which can impact on different aspects of brain function such as memory and orientation, and can include loss of consciousness.

These neurological symptoms typically resolve spontaneously with appropriate management over a short period of time (7-10 days) however recovery times vary from person to person.

Concussion incidents have two main mechanisms of injury; the primary (contact) incident and a secondary inflammatory response that can explain why people should be monitored closely over the first few days as people can deteriorate despite presenting with only mild symptoms at the time of injury.

CONCUSSION IDENTIFICATION:

Practitioners should be suspicious of a concussion diagnosis if one or more of the following characteristics are present after a collision or trauma incident:

- Symptoms – headache, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, blurred vision, sensitivity to light and noise

- Physical signs – slow to get up, holding the head, unsteadiness, looking dazed, loss of consciousness (blacking out in 10% of cases), loss of balance and poor coordination

- Behavioural and emotional changes – irritability, sadness, anxiety

- Cognitive impairment – slowed reaction times, difficulty concentrating, amnesia, feeling like in a fog, confusion

- Sleep disturbances – sleeping more or less than usual, insomnia

ON-FIELD ASSESSMENT:

- Assessment post head injury should include standard first aid principles (airway and breathing assessment being the main priority), then focusing on excluding cervical spine injury including midline tenderness and associated upper or lower limb neurological symptoms.

- The next step involves removing the player from the game or activity and should be assessed for a concussion using the SCAT3 or other equivalent side-line assessment tool.

- If a concussion is suspected, the patient should be monitored closely and referred to a medical practitioner (Doctor) for assessment. If there is doubt in management or symptoms worsen, the patient should be sent to hospital for thorough evaluation.

- The injured player should not be left alone and should be closely monitored over the initial few hours in particular and regularly checked over the first few days for symptom deterioration.

MEDICAL EVALUATION OF CONCUSSION:

All concussions require evaluation by a medical doctor. The consultation will include:

- A comprehensive history and detailed neurological examination

- A determination of the clinical status of the athlete

- Simple neurocognitive tests (if/where available)

- A determination of the need for neuroimaging in order to exclude a more severe brain injury involving a structural abnormality

The current International Consensus recommends the use of the SCAT3 for adults and youths aged 13 and over (or Child SCAT3 for younger individuals) which involves assessment of a range of areas above including clinical symptoms, physical signs, cognitive impairment, sleep disturbances, balance and neurobehavioral features that can easily be completed on the sidelines or within a clinical setting.

DO WE NEED TO SCAN CONCUSSED PATIENTS?

Imaging modalities such as Brain CT (or where available MRI brain scan) contribute little to the majority of concussion assessments, however should be employed whenever suspicion of an intracerebral or structural lesion (such as internal bleeding or potential skull fracture) exists. Examples of these situations can include prolonged loss on consciousness, focal neurological deficits or worsening of symptoms including severe headache, nausea and vomiting.

EXPECTED RECOVERY:

Between 80-90% of concussions resolve in a short 7-10 day period, although the recovery time may be extended in children and adolescents, those with complex injuries or a history of multiple concussion incidents.

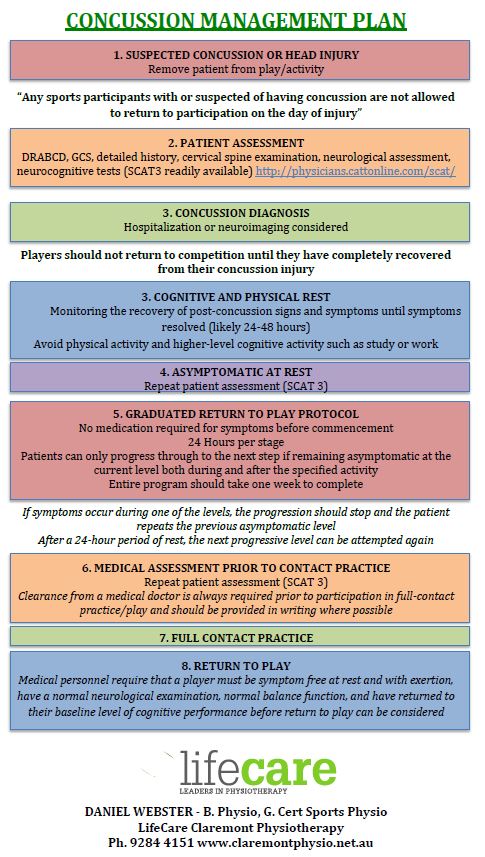

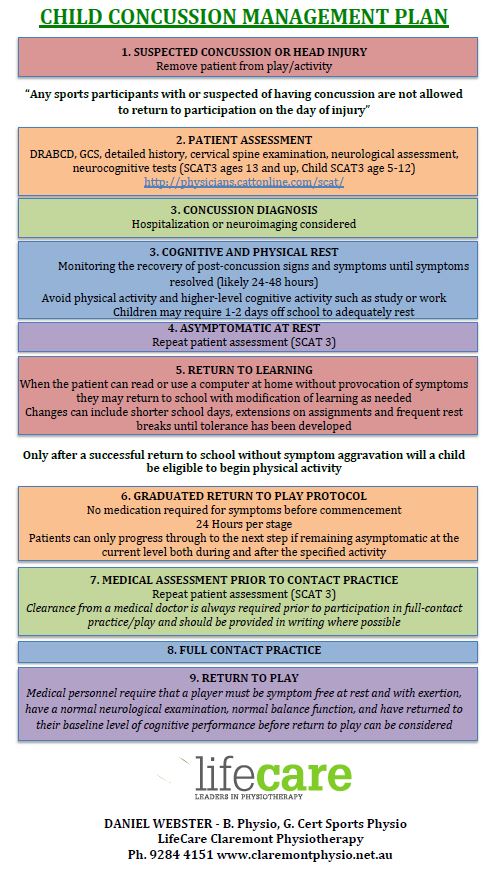

Once an athlete has been cleared of serious injury from a medical perspective the decision regarding return to play is determined by their symptoms and a controlled rehabilitation program both physically and cognitively. Expert consensus guidelines recommend players should not return to competition until they have completely recovered from their concussion injury. Clinical experience along with honest patient reporting is required to guide the recovery process that includes:

- An initial period of cognitive and physical rest to aid in recovery (24-28 hours in most cases but may be longer)

- Monitoring the recovery of post-concussion signs and symptoms

- The use of neuropsychological tests (i.e. SCAT 3) to estimate and evaluate recovery of cognitive function

- A graduated return to activity once asymptomatic with close monitoring for symptom recurrence (see below)

- A final medical clearance before resuming full contact training and/or playing

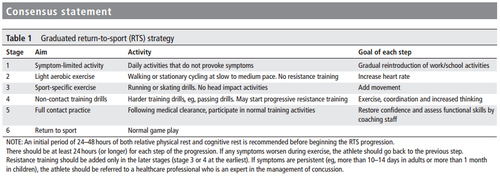

Graduated Return to Play Protocol:

The rules to following this protocol require the athlete to remain asymptomatic at each level before progressing forward, meaning that the concussion symptoms have completely resolved before returning to any physical activity (or higher level cognitive activity such as study or work). If a patient requires medication for their symptoms that may alter or mask their concussive symptoms (influence the evaluation of a persons ability), they may not commence the rehabilitation program until that medication is no longer required.

Source: Table 1. McCrory et al. (2017), p. 840.

Each step should take 24 hours so that potential delayed symptoms can be evaluated, even if clear during the increased activity, with the entire program taking a week to complete from the day they become asymptomatic to full return to sport. Patients can only progress through to the next step if remaining asymptomatic at the current level both during and after the specified activity.

If symptoms occur during one of the levels, the progression should stop and the patient repeats the previous asymptomatic level. After a 24-hour period of rest, the next progressive level can be attempted again. It is important to note that clearance from a medical doctor is always required prior to participation in full-contact practice to allow a successful return to sport.

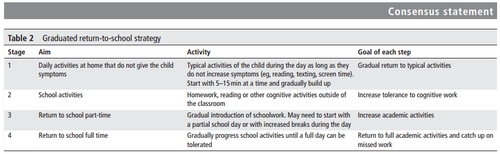

COGNITIVE MANAGEMENT:

Any person who sustains a concussion requires cognitive rest and mental workload should be reduced to allow adequate recovery. Students and workers may need to avoid the use of technology such as computers and phones, and sustain from cognitive as well as physical challenges. People require reduced workloads and may need extended rest periods (away from work or school) and avoid these tasks whilst recovering from their injury. The treating physician can guide this process and help determine the appropriate time to increase activity in a similar manner to the exercise progressions.

CONCUSSION IN CHILDREN:

The current evidence base outlines that younger athletes take longer to recover than adults with an increased risk of damage if returning to sport prematurely, especially on the same day of injury. A conservative approach is recommended for individuals under 18 years of age regardless of the level of competition or activity demands. A child SCAT3 has been developed to assess concussion for individuals aged 5–12 years, with the SCAT3 utilized for those 13 years and older.

The priority for children diagnosed with concussion is a successful return to school and learning prior to sport. Children may require 1-2 days off school to adequately rest, however others may need longer for symptoms to settle. When the patient can read or use a computer without provocation of symptoms, they may return to school. Modifications may be needed in collaboration with parents and teachers to allow a gradual re-introduction of cognitive tasks. Changes can include shorter school days, extensions on assignments and frequent rest breaks until tolerance has been developed. Only after a successful return to school without symptom aggravation will a child be eligible to begin physical activity and commence the return to play protocol above.

Complex Concussion Management:

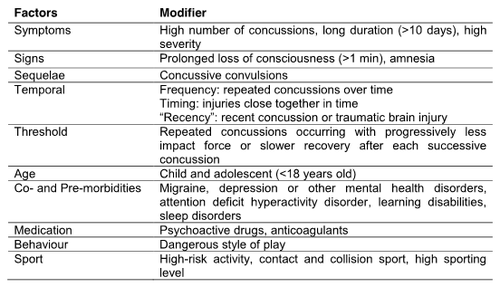

The presence of any modifying factors after a concussive injury requires a more conservative approach, including thorough assessment and a slower return to school or sports participation. In difficult or complicated cases, a multidisciplinary team approach should be considered including:

- A referral to neuropsychologist and/or doctor with expertise in managing concussion patients

- A physiotherapist with concussion rehabilitation experience to coordinate a neuro-rehabilitation program and graded asymptomatic exercise program

- A psychologist/psychiatrist if there are prominent symptoms of depression/anxiety or barriers to increasing activity levels.

References

AFL Medical Officers Association. (2013). Guidelines for the management of concussion in Australian Football for General Practitioners. Available from:http://www.aflcommunityclub.com.au/fileadmin/user_upload/Coach_AFL/Injury_Management/2013_AFL_Concussion_Guidelines__GPs_v4.pdf.

Giza, C., Kutcher, J., Ashwal, S., et al. (2013). Summary of evidence-based guideline update: Evaluation and management of concussion in sports: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology, 80, 2250-2257. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828d57dd

Harmon, K., Drezner, J., Gammons, M., et al. (2013). American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement: concussion in sport. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 47, 15-26. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091941

McCrory, P., Meeuwisse, W., Dvrak, J., et al. (2017). Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 5th international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51, 838-847. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097699

McCrory, P., Meeuwisse, W., Aubry, M., et al. (2013). Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2012. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 47, 250-258. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092313