Tim Barnwell, APA Sports Physiotherapist

What is a frozen shoulder?

Frozen shoulder, also known as adhesive capsulitis, is a condition that affects your shoulder joint and usually involves the gradual onset of severe and disabling shoulder pain, coinciding with a loss of range of motion of the shoulder [1].

The condition can last from 12-18 months, with some cases lasting up to four years.

In most cases, normal range of motion will return [2].

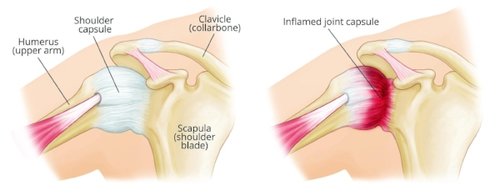

With frozen shoulder, the shoulder capsule becomes so thick and tight that it’s hard to move. The shoulder capsule is the tissue surrounding your shoulder joint that holds everything together.

The shoulder is made up of three bones: The clavicle (collarbone), the scapula (shoulder blade), and the humerus (upper arm bone).

The shoulder has a ball-and-socket joint. The round head of the upper arm bone fits into this socket. Connective tissue, known as the shoulder capsule, surrounds this joint. Synovial fluid enables the joint to move without friction.

Image source: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

Symptoms, causes and diagnosis

The main symptoms of a frozen shoulder are pain and stiffness, for no apparent reason, that make it difficult or impossible to move the shoulder.

The pain may feel worse at night or in cold weather.

Frozen shoulder is thought to happen when scar tissue forms in the shoulder, which causes the shoulder joint’s capsule to thicken and tighten, leaving less room for movement.

The exact cause cannot always be easily identified.

However, most people with frozen shoulder experience immobility as a result of a recent injury or fracture.

It’s not clear why some people develop it, but some groups are more at risk.

Females aged 40 to 65 are most likely to be at risk of developing a frozen shoulder, along with anyone who has had a frozen shoulder previously on the other shoulder.

It is also more common in those who are sedentary rather than active [3].

The condition is also common in people with diabetes and thyroid disease.

Frozen shoulder can usually be diagnosed with an examination by a GP or physiotherapist, usually along with an x-ray and ultrasound of the shoulder.

Three phase course of the condition

- Freezing – You develop a pain in your shoulder any time you move it, and your range of shoulder movement is reduced. It slowly gets worse over time and may hurt more at night. This can last anywhere from two to nine months.

- Frozen – The pain might be less but your shoulder stiffness gets worse and moving your shoulder becomes more difficult. This stage can last anywhere from four to 12 months.

- Thawing – Your range of motion starts to go back to normal. This can take anywhere from five months to two years.

Treatment options

Though the reasons for the development of frozen shoulder remain unclear, a range of treatment options are available that are suitable for each phase of the condition:

- An injection of corticosteroid in the shoulder can provide good pain relief and assist function in the early stages but does not treat the cause of the pain [4]

- Oral steroids can provide short-term pain relief [5]

- Acupuncture can also be beneficial to reduce pain in the freezing stage and to improve mobility in the thawing stage

- A sports physiotherapy program can help improve mobility

- Surgical intervention can help in long-term cases where the other treatments have not successfully resolved the issue

The benefit of exercise

Physiotherapy is widely recommended as treatment for frozen shoulder.

As the scapula can be disrupted due to a frozen shoulder, exercises to correct its movement can be useful.

Functional exercises have been shown to reduce the incidence of shoulder pain [6].

This involves physical treatment, with a long-term supervised exercise program incorporating strengthening and stretching exercises and reassurance about the activities you can undertake and continued exercise.

A recent study found that patients with a positive expectation of treatment had a better outcome [7].

If you are experiencing the early signs of frozen shoulder, book a consultation now with your local Lifecare physiotherapist to discuss the treatment options that are right for you.

- [1] Kelley et al., 2013)(Neviaser & Hannafin, 2010)

- [2] (Kelley et al., 2013)

- [3] (Neviaser & Hannafin, 2010)

- [4] (Neviaser & Hannafin, 2010)

- [5] (Neviaser & Hannafin, 2010)

- [6] (Swanik, Swanik, Lephart, & Huxel, 2002)

- [7] (Chester, Jerosch-Herold, Lewis, & Shepstone, 2016)

References:

- Buchbinder, R. (2004). Effect of arthrographic shoulder joint distension with saline and corticosteroid for adhesive capsulitis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 38(4), 384–385. http://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2004.013532

- Chester, R., Jerosch-Herold, C., Lewis, J., & Shepstone, L. (2016). Psychological factors are associated with the outcome of physiotherapy for people with shoulder pain: A multicentre longitudinal cohort study. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 269–275. http://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096084

- Favejee, M. M., Huisstede, B. M. A., & Koes, B. W. (2011). Frozen shoulder: The effectiveness of conservative and surgical interventions-systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 45(1), 49–56. http://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2010.071431

- Hickey, D., Solvig, V., Cavalheri, V., Harrold, M., & Mckenna, L. (2018). Scapular dyskinesis increases the risk of future shoulder pain by 43% in asymptomatic athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(2), 102–110. http://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-097559

- Neviaser, A. S., & Hannafin, J. A. (2010). Adhesive Capsulitis. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 38(11), 2346–2356. http://doi.org/10.1177/0363546509348048

- Swanik, K. a, Swanik, C. B., Lephart, S. M., & Huxel, K. (2002). The effect of functional training on the incidence of shoulder pain and strength in intercollegiate swimmers. J. Sport Rehabil., 11, 140–154. http://doi.org/10.1123/jsr.11.2.140