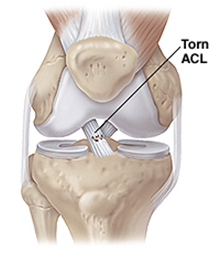

The anterior cruciate ligament, or ACL, is one of the primary passive stabilisers of the knee joint.

The primary role of the ACL is to resist excessive sliding and rotation movements of the knee, whilst also providing feedback on the joint position to the brain.

As any follower of sport would know, this injury is common. It is likely that you know someone who has suffered this injury, or seen a player suffer this injury playing sport.

A recent high profile example is Robert Murphy of the Bulldogs, who ruptured his ACL in the 2016 AFL season (see below).

Figure 2. Robert Murphy knee injury (source: heraldsun.com.au)

Statistics show that ACL injures are the most common knee ligament injury, carrying a significant impact relating to loss of function and playing time.

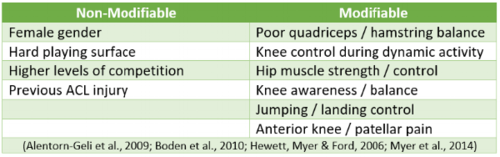

The factors contributing to ACL injury have been well researched, with risk factors considered non-modifiable and modifiable.

The figure below lists some of these common factors.

While we can’t change the unavoidable variables, for example, the hardness of the pitch you are playing on (1), there is evidence to show some factors can be influenced.

Whilst studies differ on the variables which can be modified, a number of them include:

- Poor quadriceps/hamstring muscle balance – Studies show when athletes have weaker hamstrings in relation to their quadriceps they exhibit a higher risk of ACL injury (1, 2).

- Knee control when moving is shown as a significant risk factor for ACL injury, particularly movement of the knee inwards with or without rotation inwards (2).

- Hip muscle strength and control affects knee control (see above), with studies showing reduced activation of some hip muscles alters control and increases ACL injury risk (1, 3).

- Knee proprioception describes the knee balance and awareness. When this is reduced or impaired for a variety of reasons, this can increase ACL risk (3).

- Jumping/landing control – Studies show that knee and foot position when landing in particular can affect ACL injury risk (2).

- Anterior knee/patellar pain – Evidence shows that pain around the anterior knee (e.g. patellofemoral pain) increases the risk of ACL injury (4).

Figure 3. ACL risk factors.

This list is in no way exhaustive; however, these are a number of the key factors which could amplify an individual’s risk of suffering an ACL injury.

Positively, the modifiable risk factors can be influenced by completing targeted strength and control exercises.

Studies demonstrate positive results in relation to reducing the number of ACL injuries when individuals complete targeted injury prevention programs (1, 5, 6).

If any of the modifiable risk factors mentioned above sounded familiar to you and how you move, it is recommended to consult a Lifecare Physiotherapist with a view of commencing an injury prevention program.

Book an appointment with your local Lifecare physiotherapist.

Written by Ky Wynn, Physiotherapist